|

|

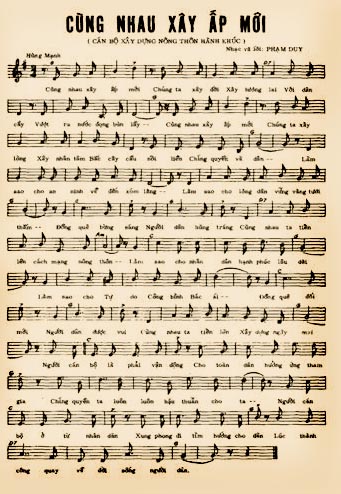

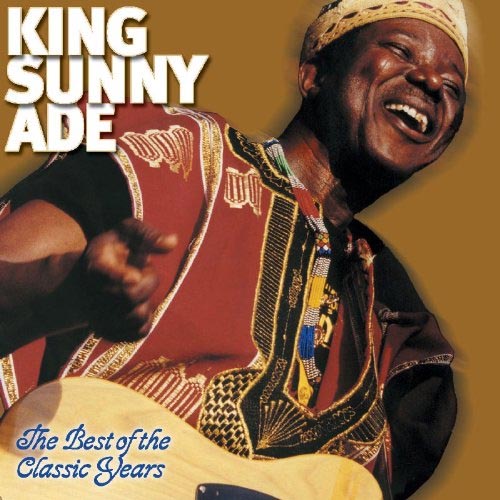

In the late 1980s, newspapers in the U.S., U.K. and Africa carried reports about a propaganda record secretly financed by the United States government and performed for Nigerian audiences by Sunny Ade. The U.S. government had invested $350,000 in the production and promotion of the record album, titled "Wait For Me," which urged Nigerian listeners stop having babies. It seems an outrageous goal for the US to pursue clandestinely but, in fact, a huge proportion of US "development" aid to the southern hemisphere consisted of activites intended to slash birthrates among peoples where the practice of birth control has little popularity. Other than military assistance and training, in several countries (Nigeria especially) virtually every cent spent on population project – public outreach, clinica training, and government "policy development" campaigns, along with a little (very little) something "nice" to take away the bad taste. The reasons for the extraordinary concern in Washington have always been related to cold war ambitions. The colonial and early post-colonial years had produced an era of "third world nationalism," and heroic figures emerged who articulated the demands of their people in ways that sent shivers down the spines of western leaders. There was Achmed Sukarno in Indonesia, Mohammad Mossadegh in Iran, Sekou Toure in Guinea, Ho Chi Minh in Vietnam, Fidel Castro in Cuba, Patrice Lumumba in Congo, Nelson Mandela in South Africa, Kwame Nkrumah in Ghana, Muritala Muhammed in Nigeria, Jacobo Arbenz in Guatemala, Salvador Allende in Chile, and Anastasio Somoza in Nicaragua, to name some of the best known. And all of them relied on large, growing and youthful populations to stand up to the old colonial regimes and reclaim their independence and national identity. But in Washington and London, this groundswell of independence was interpreted as the beginning of a worldwide "communist inspired" revolution and the loss of access to "strategic and criticial" minerals, not to mention disruption of trade agreements that favored the strong and powerful, among other things. The military for military reasons and the intelligence communities for political reasons, all insisted that these nationalist movements be contained both immediately (coup plots and assassinations) and over the long term. Curbing demographic growth perfectly suited every one of their purposes. In Nigeria, the funds for the controversial Sunny Ade recording were distributed through a U.S.-government intermediary, the Baltimore-based Johns Hopkins University, along with several other subcontracting institutions, and the source and purpose of the money was carefully concealed not only from the Nigerian public, but even from Ade himself. The use of professional musicians in American propaganda efforts is nothing new. And the Ade project follows a precedent as old as the cold war. (See, at right, sheet music intended for use in Vietnam to "persuade" villagers to relocate to internment camps) In the early 1990s, government censors finally cleared for release the files of what is believed to be the first organised effort to recruit musicians to participate in clandestine ideological influence campaigns against foreign subjects. The records consist of a series of formerly-classified U.S. Army staff reports and memoranda prepared in 1953 and 1954. An 11 August 1953 memorandum notes, for instance, that popular musicians recruited from with "target" populations "can be a valuable source of information for Army psychological warfare units" and can provide for the U.S. propaganda machine "an effective reservoir of talent for broadcasts using music." The formerly-confidential memo, which was declassified in August of 1992, was directed to the Army's "Chief of Psychological Warfare" and to Col. John B. Stanley, who headed the "psy-war" Requirements Division. It was written by Carleton F. Scofield, Assistant Director of the Army's Psychological Warfare Research Division. The document reported that other agencies had used foreign musicians for broadcasting operations "occasionally in the past," but stated that there had been "no systematic effort to contact such people and utilise their talents." It recommended a "pioneering" effort to induce entertainers to participate in American propaganda operations on the grounds that such a programme "would provide a continuing and useful flow of intelligence for operators in the field," and because it "might vastly increase the effectiveness of psychological warfare programmes using music." The recommendations were the result of a secret research operation with the code name "project TREBLE," intended to evaluate the possibilities for recruiting foreign performers into American cold war intelligence and broadcasting activities. "Recently defected musicians have an intimate and fresh knowledge about many aspects of music in target countries, especially the style and types of music which are popular," the memo stated. "Psychological warfare operators lacking current information of the kind known to such musicians run the risk of broadcasting music which is no longer popular with the audiences they are attempting to reach," it added. The communique, part of a much larger file of records from the Army's Psychological Warfare Division, suggested almost unlimited possibilities for the concept of incorporating musicians into cultural and political programming for foreign audiences. Such "defectors," it continued, "would have information which could suggest new psychological warfare themes involving the use of music." They might likewise "be used in several ways to improve the effectiveness of music broadcasts. They can supply operators with compositions valuable for psychological warfare which are not available on records" or even provide "live broadcast" capability. "Many compositions of value for psychological warfare (especially folk music and music by native composers of the target country) have never been put on discs," advised the early cold war strategy paper. Above all, the use of "collaborator" musicians would give propaganda campaigns much-needed credibility, the Army experts concluded. It explained: "[P]erformers – especially singers – would be veritable magnets for attracting listeners to U.S. broadcasts. They know the style and type of music preferred by their fellow citizens, and can `speak' to them in their own language. Many recordings of indigenous music recommended in the TREBLE report are performed by Americans who have little knowledge of, or feeling for, the style familiar to target audiences. Others, performed by native artists but recorded in the U.S., have been Americanised in some way – in style, words, instrumentation, etc. Both types are far less useful for psychological warfare purposes than performances by artists who have the immediate feel of their native land." The 1953 documents concern themselves primarily with communist countries, and they clearly referred to "psy-war" broadcast operations that were openly sponsored by the United States. The Ade case is even more subversive. Audiences were never intended to know that the United States had orchestrated the Ade record as part of a "psy-war" offensive – precisely because the purpose was to deceive the Nigerian people into thinking that the ideology it conveyed was spontaneous. The Nigerian project, in other words, was covert. The source was concealed. It exemplifies a now-familiar strategy of issuing falsely-attributed information as a means of persuading an audience to accept ideas that they would immediately reject if they knew the source or the purpose. And while the entertainers sought under "Project TREBLE" plans were to be "agents" in the true sense of the word – that is, they would openly change their national allegiances – modern "psy-war" and espionage operations often use what American bureaucrats call "in-place defectors" – agents planted in strategic positions whose links to foreign powers are not known. Ade, however, was neither. Indeed, he himself had been deceived by the U.S. government. A written agreement between him and the Johns Hopkins University makes no mention of the project's U.S. sponsorship, and Ade confirmed in a June 1990 interview with a Washington reporter that he had no knowledge the money he was paid to make the record came from the U.S. government. Of additional significance is the fact that the Nigerian propaganda recording was part of a far larger mission to infiltrate virtually all indigenous communications – from commercial entertainment to traditional folk media, local broadcast facilities, social and religious institutions, schools, public ministries, business establishments, and even art – to advance the ideological purposes of the United States. And, last but not least, propaganda planners know that an illogical message can only be made credible and acceptable to its intended audience if they can cause it to repeated almost incessantly until the public is lulled into accepting it as an ordinary and reasonable belief. In fact, there is an old saying among public relations people that the message heard the most is the one that is believed. If a theme is repeated often enough, in other words, it sinks into the minds of listeners at the subconscious level, and the ability of the target audience to counter it is eroded. Were this not the case, it would be hard to understand the collossal amounts of money spent on broadcasting the same propaganda day after day through government operations like Radio Liberty (targeting the USSR) and Radio Free Europe (playing to Soviet satellite nations) or the "white propaganda" campaigns of the Voice of America worldwide. The use of commercial music records like the Nigerian example thus becomes an especially powerful weapon in the hands of "psy-war" operators. A song can be repeated over and over on radio a lot more easily than can a recorded testimonial or other broadcast spot. And the repetition of a musical selection attracts less curiousity among listeners than would a repeated announcement. Messages carefully planted in modern music are, in a sense, the "stealth bombers" of contemporary psychological warfare. Psychological warfare is a concept as old as the cold war. Another recently-released memorandum from the Army psychological warfare division, titled "Guidance for Military Psychological Warfare Research and Planning" and dated 1 July 1954, defines "psy-war" as follows: "In broad terms, modern military psychological warfare can be defined as the planned use of propaganda and other actions that have the primary purpose of influencing the opinions, emotions, attitudes and behaviour of enemy, neutral, or friendly foreign groups in such a way as to support the accomplishment of national aims and objectives." Although the music-oriented "Project TREBLE" was specifically directed at communists and communist sympathisers, U.S. military "psy-war" activities had long been carried out against "third world" targets, as well. An even older communique – dated 14 September 1951 – appears in the records of the Plans & Operations Division of the Army's Signal Intelligence Agency. It requests that officers of the "Materiel Branch" conduct surveys to "elicit functional intelligence for use in Psychological Warfare Planning and to furnish Psychological Warfare officers in overseas commands with a basis for planning radio broadcasting operations." The intelligence was to cover 36 countries in every part of the world except Latin America. Four North African nations appear on the list: Morocco, Algeria, Libya, and Egypt. The paper trail from Project TREBLE to the Johns Hopkins-Sunny Ade project never grows cold, although it goes through several high-level U.S. government agencies. In the aftermath of the second World War, the University worked on a top secret program with the U.S. Army to develop the first teaching manual on the technique. Alfred H. Paddock, Jr., in his book US Army Special Warfare; Its Original, Psychological and Unconventional Warfare, 1951-1952 (1982) explains: To conduct nonmateriel research in support of the burgeoning psychological warfare effort, the Army relied almost exclusively upon a civilian agency, the Operations Research Office (ORO) operated under a contract by the Johns Hopkins University. Studies by ORO included a three-volume basic reference work for psychological warfare, manuals for use by psychological warfare operators in specific countries, an analysis and grouping of sample leaflets from World War II and Korea to develop classification schemes, and a large amount of field operations research in Korea. (Paddock, at pages 116-117) Specifically, the university's off-campus Operations Research Office, under the direction of Dr. Ellis A. Johnson, produced for the military such documents as A Psychological Warfare Casebook, a "technical memorandum" titled U.S. Psywar Operations in the Korean War, and similar reports, Evaluation and Analysis of Leaflet Program in the Korean Campaign – June-December 1950 and An Evaluation of Psywar Influence on North Korean Troops, dated 1951. Another early assessment of the psychological warfare campaign measured the "value of propaganda leaflets disseminated by aircraft." And the JHU Operations Research Office also published Eighth Army psychological warfare in the Korean War in 1952. In August of 1952, the Psychological Strategy Board, an organ of the National Security Council, sent a hand-delivered memo to General William Draper in Paris, requesting assistance in the development of a "long-range U.S. psychological strategy" which "would concern itself specifically with colonial territories in Africa South of the Sahara." Draper was then the government's special representative in Europe for the Mutual Security Agency. About six years later, he was appointed by President Dwight Eisenhower to head a commission to study the U.S. foreign military assistance programme. The Draper committee's report, released in mid 1959, was the first official, unclassified document to urge that the government embark upon a campaign of population control on national security grounds. However, the report stopped short of calling for "psy-war" programmes to reduce birthrates. Indeed, it was not until 1965 – nearly six years later (and after several other military and industrial leaders had expressed similar opinions) – that the government began a formal population control programme. Early efforts sought primarily to bring birth control clinics and supplies to developing countries. Over the next eight or nine years, it became apparent that the "supply-side" approach was working in a few countries, but had produced virtually no change in the behaviour of the majority of the developing world's people. And so it was back to the drawing board. Finally, in 1974, a comprehensive plan was developed for the implementation of population control throughout the southern hemisphere – a plan which put propaganda and "psy-war" techniques at the heart of the population programme and called for the deployment of a broad spectrum of government agencies. The study, prepared with the assistance of the Central Intelligence Agency, the Department of Defence, and the State Department, urged that U.S. Information Agency (Voice of America), United Nations, and Agency for International Development (USAID) capabilities be enlisted to "motivate" people to use western anti-fertility drugs, and even called for a revision of World Bank operating guidelines to allow full financing of birth control activities abroad. "Beyond seeking to reach and influence national leaders, improved world-wide support for population-related efforts should be sought through increased emphasis on mass media and other population education and motivation programmes by the UN, USIA (US Information Agency) and USAID," the 10 December 1974 document stated. It acknowledged that many countries "fear unwanted propaganda and subversion by hostile broadcasters" and that "the US must tread very softly when discussing assistance in programme content," but nonetheless concluded that the ability of USIA "to convey information on population matters should be strengthened to a level commensurate with the importance of the subject." The same 1974 study targeted 13 of the world's largest developing countries for special attention under the population programme, including Nigeria. That memorandum remained classified for nearly 16 years, and was finally released after the Ade record deal had been consummated. A follow-up study, compiled at the National Security Council level and presented to the Council on 3 January 1977, explicitly called for a "mass media" operation that would consist of "interpersonal contact, meetings, TV, radio, posters, pamphlets, puppet shows, traditional theater" and other forms of "persuasion."

Like assassinations and and coups directed at popular leaders in developing countries, this was to be the targeting of their followers. Fewer revolutionaries, they assumed, would mean fewer revolutions or at least weaker ones. That's what's referred to in Pentagon-speak as "long range planning." The report was ignored during President Jimmy Carter's term in office, but became the dominant strategy for Africa under both Ronald Reagan and George H. W. Bush. About $10 million was spent by USAID for a single ideological research project, contracted to Johns Hopkins, between 1982 and 1986. And in 1986, an additional $30 million was provided to Johns Hopkins to begin the active phase of the aggressive contraceptive indoctrination effort. The money that funded the Ade record and promotional campaign came from a separate account – a $15 million slush fund set up in 1988 entirely for Johns Hopkins' activities in Nigeria. Ironically, the contract for the Nigerian offensive echoes the language of the secret 1977 communique, calling for "exploiting fully traditional media, such as town criers, talking drums, dances, songs, drama troupes, and puppet shows," as well as the use of such modern media as "popular radio and television series," print publications, and film. And like Project TREBLE almost forty years earlier, it stresses the need to recruit local musicians who can address target audiences in their own language. It makes the university responsible for conducting "rapid anthropological research ... involving the major Nigerian ethnic groups ... for use in producing regionally-distributed materials," and for "undertaking a music project nationally and by region to the end that popular songs containing family planning themes are composed and recorded by popular local musicians, and distributed and aired." |

| |

|

Tweet

|